Granny’s Brown Bread

SCÉAL #07 - Recreating my granny’s brown bread as a birthday treat.

This weeks email is an ode to my Grannys brown bread, but first I’d just like to cover a little housekeeping. Just popping on to remind you that we are baking this Friday, 9th June. Doors at the Fumbally Stables will be open around 10 am. Charlotte is baking a beautiful seasonal galette with apricots and thyme infused honey. I will sneak some savage sourdough pan de cristal onto the bread lineup too. Keep an eye on the ould Insta-stories for sneak peaks and menu updates.

We are then taking 2 weeks annual leave. We are trying to lock down additional bake and workshop dates, TBC soon. We’d like to extend our giant gratitude with the patience everyone has shown us in the sporadic nature of our work/bake schedule for the last year while we’ve worked on our next project. There has been some progress in the last two weeks. Things are at least moving in the right direction for us. We had no idea when entering into the process of growing the business that we’d get caught up in a long chain of bureaucracy. We will have more on this soon. Thank you as always, Charlotte & Shane xxx

Granny

My Granny had the good sense, even back then, to call these “her cakes”. Not bread but more accurately cakes. She had a huge family. My mother is one of 17 kids. My Grandmother would often make 6 cakes a day. 3 brown cakes and 3 “curreny cakes”, as she’d call them, a white soda bread with currents and butter in it.

Granny always landed a slice of brown bread down in front of you the minute you sat at the kitchen table. A nice thick slice with an even thicker slice of butter, smothered in honey. It was such a treat you’d be forgiven for thinking it was cake.

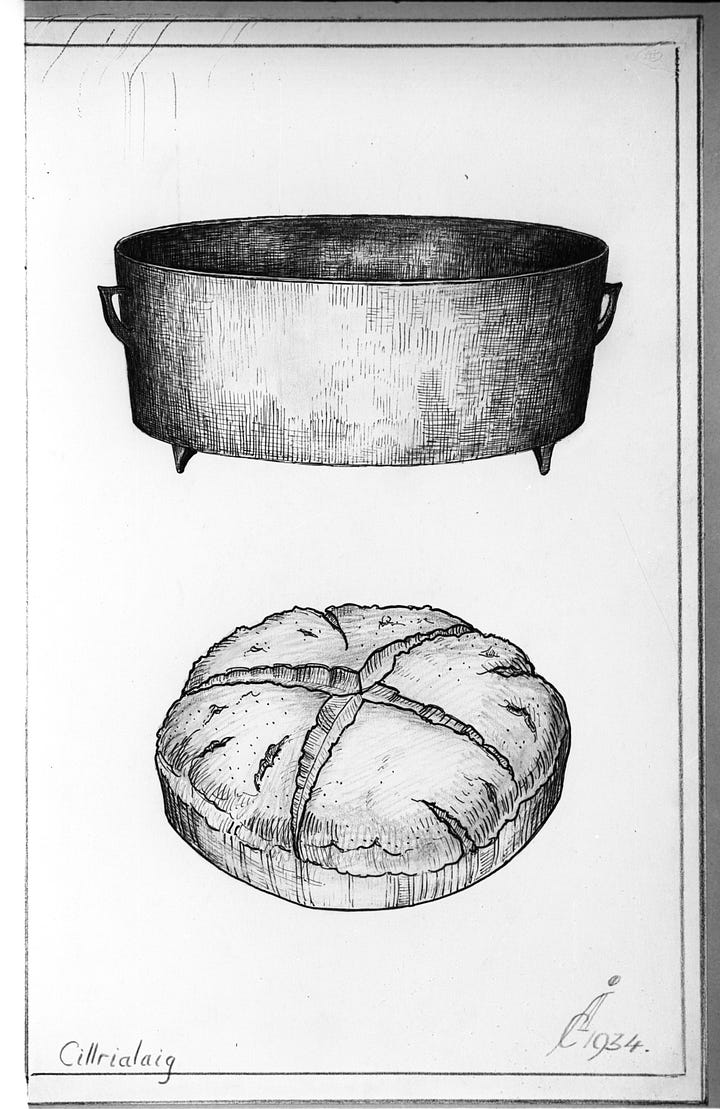

She had a magical touch when mixing the flours, being mindful to incorporate air while mixing the baking soda and salt, before adding the buttermilk. Gently bringing the dough together and forming a soft pillowy round with her floury hands.

I recently turned 37. I’m ashamed to say I have never been able to even come close to recreating this brilliant bread that nourished me as a child and sparked the curiosity in me to become a baker. Part of me has accepted the fact that no matter how hard I try, I will never be able to make a soda bread as good as my granny’s. She would have had 30 years experience on me before I was born and another 26 before I started baking. Baking 3-4 soda breads every 2 days on average, that’s a whopping 60,000 breads baked before I even set foot in a professional kitchen.

As I sit writing this, my second attempt at her recipe is cooling beside me wrapped in a tea towel. Steaming her darkly baked bread in a cloth allows for a soft crust. This was one of the essential steps in the long list of instructions sent to me on my birthday by my Uncle Dominic, the custodian of my grandmother’s recipe.

I tried to wait for it to cool fully and failed. I sliced a thick slice and slicked on a lush amount of salty butter. Topped it with honey and sunk my teeth marks in to pure delight. Good but not quite there yet, a bit tight, a bit dense. I’ll adjust the buttermilk I tell myself, try to be more gentle, little kneading. Practice makes perfect, even if I never perfect it. It’s the practice, the ritual, that makes these moment’s special and helps me honour a wonderfully humble human. Granny was very religious, she prayed to an alter in one of the window sills of the kitchen several times a time and said the rosary. Honouring relatives who’d passed and the bread gods.

She would cut a cross into each loaf, not so much to symbolize Jesus but as she explained “to let the fairies out”. As a child this encapsulated everything you need to know about the magic and science of baking bread. So much of superstition and tradition in Ireland are carried by stories like these.

Somehow the fairies, mischievous and curious by nature, would be trapped inside the bread during baking. By cutting the cross, you release the fairies to prevent them from casting spells or wreaking havoc in the home. This whimsical belief not only added a sense of wonder to the baking process but also served as a reminder to approach anything you do in life with a sense of respect and caution.

Soda Bread or Wheaten Bread

Charlotte, whose parents are both from Co.Down, Northern Ireland, call Soda bread “Wheaten bread”. As it’s what Charlotte grow up with, she also calls soda bread wheaten bread. For some reason I took slight offence to her calling my Grannys brown bread by this name, and a debate ensued. To settle the difference and prove one of us correct, as we often do, we turned to google and I went on a little deep dive where I dug up some differences. But as with most cultural divides, the differences seemed to hold little weight once we cut beneath the crust. These divisions are reflected not only in language and politics but also in the distinct culinary practices that have evolved over time.

Throughout history, Ireland has experienced various divisions and regional distinctions, which have contributed to the development of unique cultural identities. The disparity in naming can be attributed to historical and cultural factors that have influenced the culinary traditions of Northern Ireland and the Republic respectively. In Northern Ireland, it is commonly referred to as "wheaten bread." This regional variation of alternative names reflect the cultural nuances and historical influences that have shaped the culinary identities of the North.

In Northern Ireland, the term "wheaten bread" is commonly used to describe soda bread made with 100% whole wheat. This name stems from the primary ingredient used in this variation of the bread, which is wholemeal flour made from finely ground wheat. The name emphasises the presence of wheat in the bread, highlighting the region's strong association with agricultural practices, wheat cultivation, and traditional baking methods. The use of wholemeal flour contributes to the distinctive texture and nutty flavor of wheaten bread.

In the Republic of Ireland, soda bread is frequently referred to as "brown bread." This name reflects the common use of a combination of flours, including wholemeal and white flour, resulting in a bread with a slightly lighter color compared to wheaten bread and this reflects with my Granny’s recipe. There is an interesting archive of folklore and recipes on soda breads on the Duchas website. Unfortunately the 6 counties of the North of Ireland were never included in the collection of archive of the stories. However there are plenty of mentions of wheaten bread.

A Common Ground

Despite the differing regional names, it is important to note that the core characteristics and preparation methods of soda bread remain more or less the same throughout Ireland. The bread is leavened using baking soda, which reacts with an acidic ingredient such as buttermilk. Together they create carbon dioxide bubbles, resulting in an airy texture. The simplicity and versatility of soda bread have made it a cherished part of Irish cuisine, enjoyed across Ireland and beyond.

Despite these variations, the common thread lies in the appreciation and celebration of Irish soda bread as a symbol of the island's rich culinary heritage. Whether called wheaten bread or brown bread, this beloved bread unites people through its unique flavors, warm aromas, and shared traditions, embodying the spirit of Ireland's hard fought gastronomic legacy. But it’s not something that we have had for a long time and was brought about because of our colonial past.

Looking back at the history of soda bread from a colonial perspective tells a story of resilience, adaptation, and a kind of cultural fusion. In a way soda bread emerged as a symbol of survival, creativity and cultural appropriation in the face of challenging times.

The 18th and 19th centuries brought significant changes to Ireland as it grappled with colonisation and economic hardships. The introduction of wheat and baking soda by colonial powers revolutionised the traditional bread-making techniques that relied on oats and yeast. These new ingredients provided an alternative and more accessible means of producing bread, especially in areas with limited resources.

The arrival of wheat as a staple crop introduced by the British colonists played a crucial role in reshaping Irish baking practices. Previously, oats had been the main grain used in bread-making. However, wheat flour, with its lighter texture and versatility, gradually gained popularity among the population. It offered a means to create a more refined loaf that resembled the bread enjoyed by the upper crust in society.

Another significant transformation was the adoption of baking soda, or bread soda, in place of yeast as a leavening agent. The scarcity of yeast, combined with economic hardships, prompted Irish bakers to explore alternatives. Baking soda, which was introduced by the British, proved to be a practical solution. Its ability to interact with acidic ingredients like buttermilk to produce carbon dioxide gas resulted in a lighter and quicker bread-making process.

With limited resources and under the shadow of colonisation, we embraced these new ingredients and techniques, infusing them with the existing unique culinary traditions. The resulting soda bread retained its distinctive Irish character. Gradually soda bread became deeply ingrained in Irish culinary culture.

The bread's versatility and simplicity allowed it to be customised with various additions like seeds, nuts, or dried fruits, reflecting regional and personal preferences and practices for different holidays etc. It is difficult to assign a specific date for the emergence of soda bread. The earliest known recipe in a publication comes from an Ulster newspaper, the Newry Telegraph, in 1836, and was repeated in a London paper, The Farmer’s Magazine (O’Dwyer 2003).

As a baker, I am honored to carry forward this legacy, celebrating the rich heritage of Irish soda bread and the stubborn spirit of our ancestors. But my curiosity is naturally pulled in the direction of what style of bread were we baking in Ireland before the introduction of Soda bread. Was there ever a tradition of sourdough bread baking and was that part of our history eradicated and hidden like so much more of our culture?

The historical evidence regarding the specific existence of sourdough baking in Ireland prior to the introduction of soda bread is limited. Sourdough baking, has a long history worldwide. However, in the context of Ireland, where oats were the dominant grain for bread-making, there is less documentation of widespread sourdough traditions.

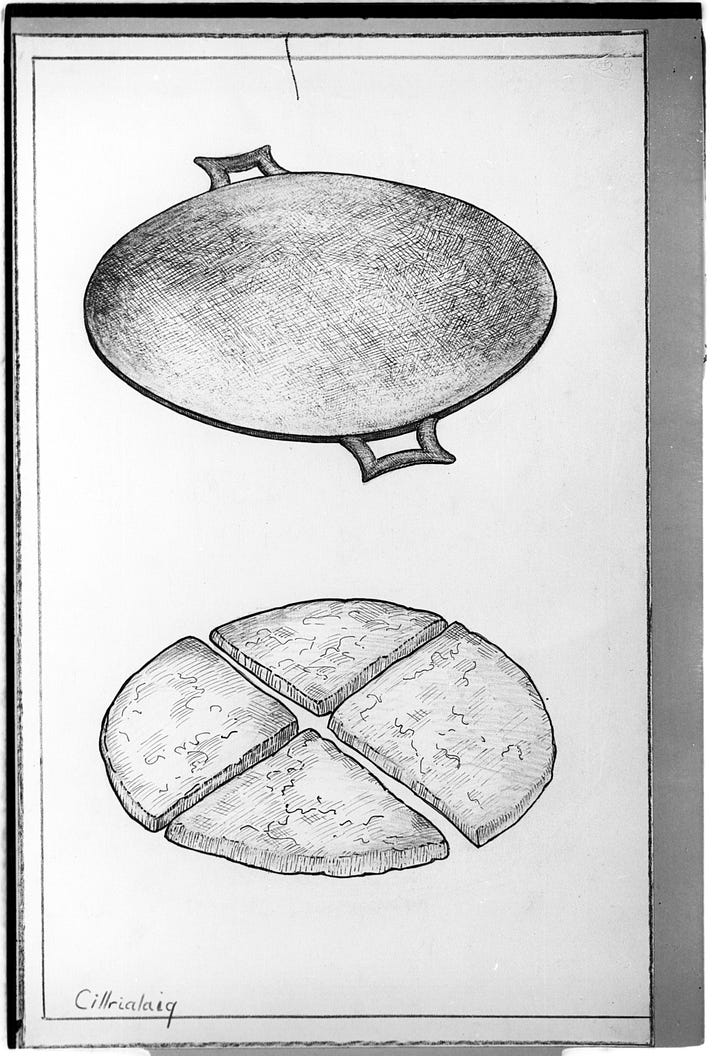

Oats, being low in gluten, do not provide the same structure necessary for a classic sourdough fermentation process. Sourdough bread typically requires a higher gluten content, which is found in wheat flours. It is worth noting that in certain regions of Ireland, particularly along the western coast, sourdough-like methods were used in preparing certain traditional dishes, such as "bannocks" or "griddle breads." These were often made with a mixture of oats and wheat or barley flour, combined with buttermilk or sour milk. While not technically considered sourdough bread, these preparations incorporated some aspects of naturally fermented doughs.

The thought process, has always been that the main issue came down to the grain grown. It’s a long standing consensus that we have an awful climate for growing wheat, therefore our flours were not the best. However, other grains grew well: barley, oats and rye were well documented. From an article in the Irish Times, “A French man visiting Ireland in 1790 noted, "In the south of Ireland bread is made with oats, in Wicklow with rye, and in Meath with a mixture of rye and wheat."

Thankfully, we now have a wide range of Irish grains and flours available again. These include ancient grains that are well-suited to our climate. Additionally, due to our warmer weather, we are witnessing successful growth of modern wheat varieties here as well. The misconception that our climate cannot support the grains necessary for extended fermentation bread, such as sourdough, is simply unfounded. A shift in thinking has taken hold and our options as bakers are opening up as the local flour economy recovers.

Looking Back to Move Forward.

Food traditions travel and evolve through time, both literally and figuratively. It can be carried by people, the animals we rear, in the air and the water we consume. And more commonly nowadays by human intervention and invention. Sometimes it lasts through the generations and becomes part of our new traditions, while other times it disappears and then comes back as a cherished memory. The way we think about food can also morph as things like our needs, preferences, and personalities change. Food truly is one of our first cultural statements.

When then does a food that used to be ordinary and part of our everyday lives become recognised and celebrated as a symbol of our culinary heritage. What happens when certain foods become important for tourism, marketing, or national pride? Is it easier to accept the past and move on? Easier to forget what we used to have and embrace our commonality we now share.

In that sentiment I happily share with you my Granny’s Recipe for her Brown Bread. This is available to all subscribers. If you would like to support our writing please consider subscribing.

Granny’s Brown Bread

Ingredients:

A large plastic basin or mixing bowl

250 grams all-purpose flour (Odlums cream flour)

250 grams Whole wheat flour

6 grams baking soda

6 grams salt

380-420 milliliters buttermilk

Instructions:

Preheat your oven to 225°C (430°F).

In a large mixing bowl, mix together the flours, baking soda, and salt until well combined using your fingertips to incorporate as much air as possible.

Make a well in the center of the dry ingredients and pour in most of the buttermilk. Reserve about 20 mils.

Mix the dough with your hands until it just barely comes together. If the dough seems dry, gradually add the reserved buttermilk until you achieve a soft and slightly sticky consistency. Avoid overmixing. The dough should be falling off your hands. pull the dough together rather than using a pushing action.

Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface and gently bring it together into a round loaf. Be careful not to overwork the dough. Gentle hands are required.

Place the loaf onto the floured baking sheet and use a sharp knife to make a shallow cross on top of the loaf. You can cut one line and two smaller lined perpendicular to this line for a taller more rounded loaf.

Bake in the preheated oven for about 35-40 minutes, or until the bread is dark golden brown and sounds hollow when tapped on the bottom.

My Granny always checked the loaf about 5 minutes before the bread is done baking, flipping it over on its top if it was getting too dark, for an even bake.

Remove the bread from the oven and transfer it to a wire rack, wrap in a damp tea towel to cool completely before slicing.

One thing I really take from this is that my grandmother wasn’t afraid to bake the bread dark for a beautiful crusty bread, something I strive for in all my bakes. I love the crispy contrast of the crust to the creamy soft crumb. Bitter from the dark bake, rising from the culture and tradition of the past.

In loving memory X